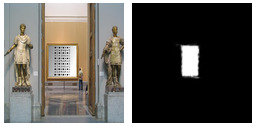

Imagine a buddy asks you to write a program to detect a simple visual pattern in a video stream. They plan to print out the pattern, hang it on the wall in a gallery, then replace it digitally with artworks to see how they’ll look in the space.

“Sure,” you say. This is a totally doable problem, since the pattern is so distinctive.

In classic computer vision, a young researcher’s mind would swiftly turn to edge detection, hough transforms, morphological operations and the like. You’d take a few example pictures, start coding something, tweak it, and eventually get something that works more or less on those pictures. Then you’d take a few more and realize it didn’t generalize very well. You’d agonize over the effects of bad lighting, occlusion, scale, perspective, and so on, until finally running out of time and just telling your buddy all the limitations of your detector. And sometimes that would be OK, sometimes not.

Things are different now. Here’s how I’d tackle this problem today, with convnets.

First question: can I get labelled data?

This means, can I get examples of inputs and the corresponding desired outputs? In large quantities? Convnets are thirsty for training data. If I can get enough examples, they stand a good shot at learning what I used to program, and better.

I can certainly take pictures and videos of me walking around putting this pattern in different places, but I’d have to label where the pattern is in each frame, which would be a pain. I might be able to do a dozen or so examples, but not thousands or millions. That’s not something I’d do for this alleged “buddy.” You’d have to pay me, and even then I’d just take your money and pay someone else to do it.

Second question: can I generate labelled data?

Can I write a program to generate examples of the pattern in different scenes? Sure, that is easy enough.

Relevance is the snag here. Say I write a quick program to “photoshop” the pattern in anywhere and everywhere over a large set of scenes. The distribution of such pictures will in general be sampled from a very different space to real pictures. So we’ll be teaching the network one thing in class and then giving it a final exam on something entirely different.

There are a few cases where this can work out anyway. If we can make the example space we select from varied enough that, along the dimensions relevant to the problem, the real distribution is contained within it, then we can win.

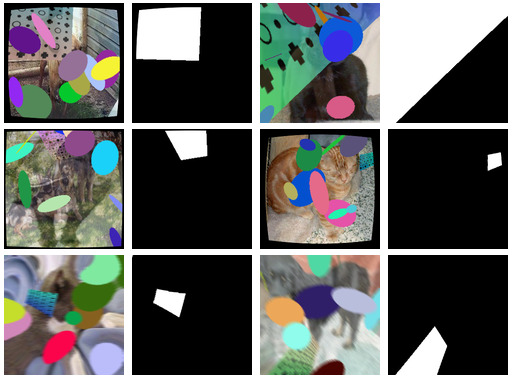

Sounds like a real stretch, but it’ll save hand-labelling data so let’s just go for it! For this problem, we might generate input/output pairs like this:

Here’s how these particular works of art were created:

- Grab a few million random images from anywhere to use as backgrounds. This is a crude simulation of different scenes. In fact I got really lazy here and just used pictures of dogs and cats I happened to have lying around. I should have included more variety. pixplz is handy for this.

- Shade the pattern with random gradients. This is a crude simulation of lighting effects.

- Overlay the pattern on a background, with a random affine transformation. This is a crude simulation of perspective.

- Save a “mask” verson that is all black everywhere but where we just put the pattern. This is the label we need for training.

- Draw random blobs here and there across the image. This is a crude simulation of occlusion.

- Overlay another random image on the result so far, with a random level of transparency. This is a crude simulation of reflections, shadows, more lighting effects.

- Distort the image (and, in lockstep, the mask) randomly. This is a crude simulation of camera projection effects.

- Apply a random directional blur to the image. This is a crude simulation of motion blur.

- Sometimes, just leave the pattern out of all this, and leave the mask empty, if you want to let the network know the pattern may not always be present.

- Randomize the overall lighting.

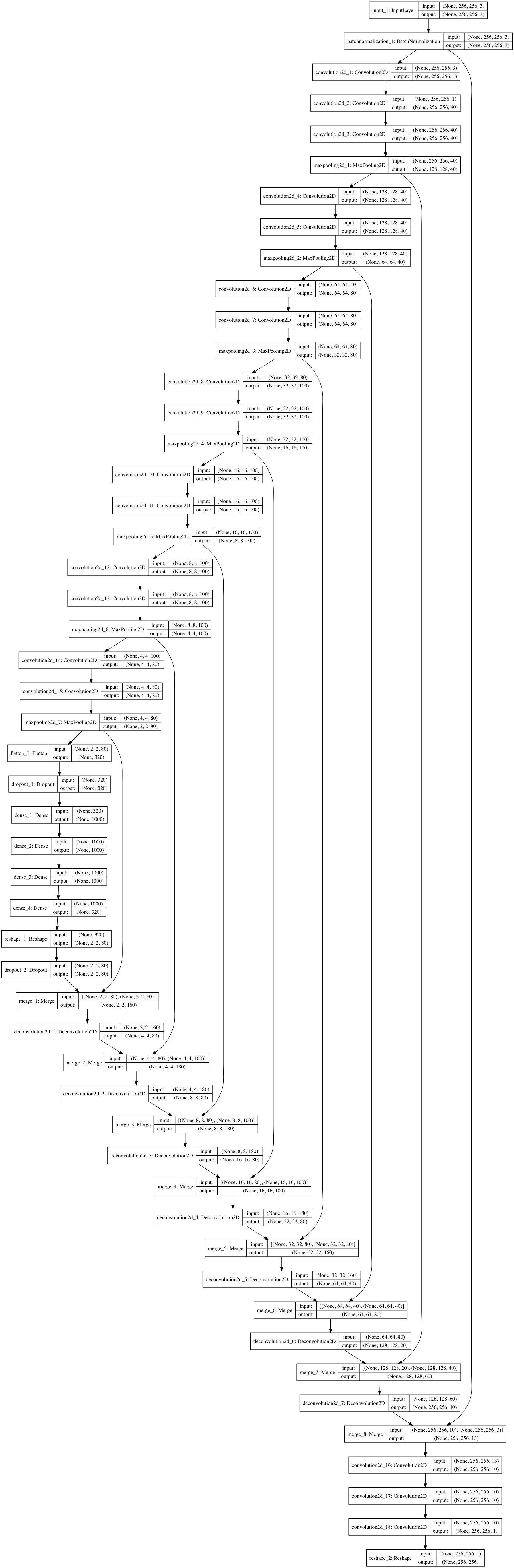

The precise details aren’t important, the key is to leave nothing reliable except the pattern you want learned. To classic computer vision eyes, this all looks crazy. There’s occlusion! Sometimes the pattern is only partially in view! Sometimes its edges are all smeared out! Relax about that. Here’s a hacked together network that should be able to do this. Let’s assume we get images at 256x256 resolution for now.

A summary:

- Take in the image, 256x256x3.

- Batch normalize it - because life is too short to be fiddling around with mean image subtraction.

- Reduce it to grayscale. This is me choosing not to let the network use color in its decisions, mainly so that I don’t have to worry too much about second-guessing what it might pick up on.

- Apply a series of 2D convolutions and downsampling via max-pooling. This is pretty much what a simple classification network would do. I don’t try anything clever here, and the filter counts are quite random.

- Once we’re down at low resolution, go fully connected for a layer or two, again just like a classification network. At this point we’ve distilled down our qualitative analysis of the image, at coarse spatial resolution.

- Now we start upsampling, to get back towards a mask image of the same resolution as our input.

- Each time we upsample we apply some 2D convolutions and blend in data from filters at the same scale during downsampling. This is a neat trick used in some segmentation networks that lets you successively refine a segmentation using a blend of lower resolution context with higher resolution feature maps. (Random example: https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.00551).

Tada! We’re done. All we need now is to pick approximately 4 million

parameters to realize all those filters.

That’s just a call to model.fit or the equivalent in your

favorite deep learning framework, and a very very long cup of coffee while training

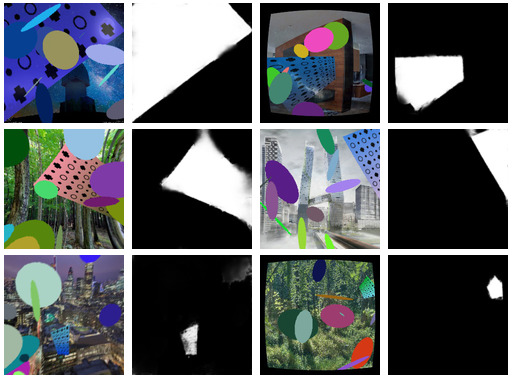

runs. In the end you get a network that can do this on freshly generated images

it has never seen:

I switched to a different set of backgrounds for testing. Not perfect by any means, I didn’t spend much time tweaking, but already to classical eyes this is clearly a different kind of beast - no sweat about the pattern being out of view, partial occlusion also no biggie, etc.

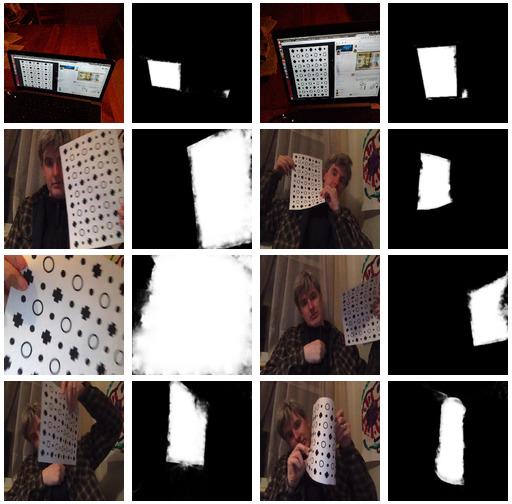

Now the big question - does it generalize? Time to take some pictures of the pattern, first on my screen, and then a print-out when I finally walked all the way upstairs to dust off the printer and bring the pattern to life:

Yay! That’s way better than I’d have done by hand. Not perfect but pretty magical and definitely a handy tool! Easy to clean up to do the job at hand.

One very easy way to improve this a lot would be to work at higher resolutions than 256x256 :-)

Code

There’s a somewhat cleaned up version of this code at github.com/paulfitz/segmenty